Bulgarian Immigrants in London: A Community of Strength, However In The Shadows

Bulgarian Immigrants in London: A Community of Strength, However In The Shadows

By Dean Bezlov, Boyko Boev, Maria Koinova, Maria Stoilkova[1] and coordinated with contributors from the London Bulgarian Association

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the Mayor of the City of London, Mr. Sadiq Khan, for his initiative ‘Citizen Led Engagement Programme for London’, that gave us the opportunity to realize our wish to learn more about Bulgarians in the UK, and the life of Bulgarians in London. We would also like to thank Mrs. Dawn Hart for her engagement with the implementation of this project. Our deep gratitude goes also to the 15 community researchers, who spent much effort and attention to conduct interviews with other Bulgarians and to deliver the data on time and in an excellent form: Adrian Apostolov, Anna Kaneva, Antonia Todorova, Borimir Totev, Dessislava Dimitrova, Dessislava Dyakova, Daniela Penkova, Ina Nikolova, Ivan Stanoev, Ivanka Zaharieva, Kalin Kalpachev, Katya Vrancheva, Kristina Kuneva, Vanya Kovacheva and Zhivko Dragostinov. This study would have not been possible without the insights of other 151 interviewed Bulgarians in London, who remain anonymous, to comply with the ethics requirements of this project. We would like to wish well to all participants in this study, and to have new collaborations in the future.

Executive summary

This is the first examination of Bulgarian immigrants living in London. It is not what statisticians would call 'a representative survey', but a study conducted on a communal basis, which aims to build a picture of the Bulgarian diaspora currently in London with the help of an open-questions survey including 151 respondents. The study was interested in exploring Bulgarian immigrants’ social status, when and why people migrated, and the scale of their integration in the UK society. Questions included topics such as their motivations and expectations about coming to London, their occupational experience, common activities and use of public facilities and resources, patterns of socialization and familiarity with neighbors, concerns with security, response to Brexit, as well as plans for the future. It would seem Bulgarians consulted for this survey, arrived in London in three main waves, in early 2000s, after 2007 when Bulgaria joined the EU, and during the economic crisis after 2009-10, when they moved from Bulgaria and in a second migration from other countries hit hard by recession, to which they have moved earlier. Most people came on their own, seeking better standard of living with some coming here to pursue further education, and only few pointing out to political reasons. Two thirds of the interviewed hold bachelor or higher degrees, with the rest having finished secondary school. And yet, despite the level of education, more than half of the interviewees were seen to change their profession upon arrival in order to find employment in London. Most Bulgarians living in London enjoy the city’s cosmopolitan life and claim they have changed for the better since arriving: they have become more tolerant, but also stressed because of the busy life, and also more secure in their lives, bringing them certain stability. At the same time many share discomfort with increased scrutiny and intolerance to foreigners. With that said, Bulgarians still explain the biggest barrier to integration and better paid jobs to be their insufficient language skills, especially problematic for older generations, learning English from scratch and balancing time as income earners. The ability to speak English appears to bear direct correlation to people’s social circle, patterns of socialization and level of integration: fluent speakers tend to be younger and well-integrated with international friends, while people who have difficulties with English tend to be of more mature age, who maintain closed social circles with other Bulgarians, often with language difficulties as well. People have some good messages for the Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, but also some complaints, mainly about discrimination and worse treatment once it is revealed they come from Eastern Europe and from public services like public transport and NHS worsening in the last few years.

Methodology

The Municipality of London communicated its methodological and ethical requirements to members of the research team and individual researchers at the end of January. Reflecting these requirements and implementing further academic and methodological insights into communal research, in February the academic team leading this study developed a detailed sheet with instructions for the 15 community researchers, to prepare them for the data collection phase. In summary, this sheet instructed the researchers to find 10 other people to interview from an equally distributed number of age cohorts, female and male genders, and to look for respondents in a variety of places in London, including contacts of the London Bulgarian Association, Bulgarian schools, stores and other places, where Bulgarians regularly meet. Community researchers were required to collect and transfer data anonymously, and on 20th February were given one month to complete their assigned 10 interviews. Support and advice was given to individual researchers during the data collection phase. Researchers were required to deliver the responses anonymously in electronic form, so that the data could be analyzed comparatively. In the analytical phase, categories of: 1) education, 2) gender and 3) age were singled out for the development of the analytical report, in addition to the development of charts and graphs to better visualize data trends.

Introduction and a brief overview of the history of Bulgarian migration to the United Kingdom

Bulgarians begun migrating to the UK ever since the Eastern Bloc disbanded in 1989. Yet, regrettably little is known about the number of migrants living in the country or their work and life habits as well as integration status. Over the years Bulgarians coming to the UK have faced a number of restrictions concerning their conditions of stay and the types of employment available for those who came, with a final abolishment of all restraints in the beginning of 2014. More recently Bulgarians (and Romanians) attracted much unfavorable attention in the British media, as immigrants from these groups found themselves at the very center of the heated debates surrounding the UK referendum on EU membership.

The study presented here is an effort of the London Bulgarian Association to collect data and offer more accurate picture on the Bulgarian immigrants living in London and their contributions to the British society. The results of this survey need to be understood in the context of the major mobility patters of Bulgarians since 1989 and in relation to the changing economic and political environment in the EU, changing migration and employment rules and policies in the UK, as well as the unintended effects that such policies have on social and cultural dynamics out of which immigrant experiences are shaped. We briefly sketch below some general trends and use them to contextualize the experiences of Bulgarian immigrants in London.

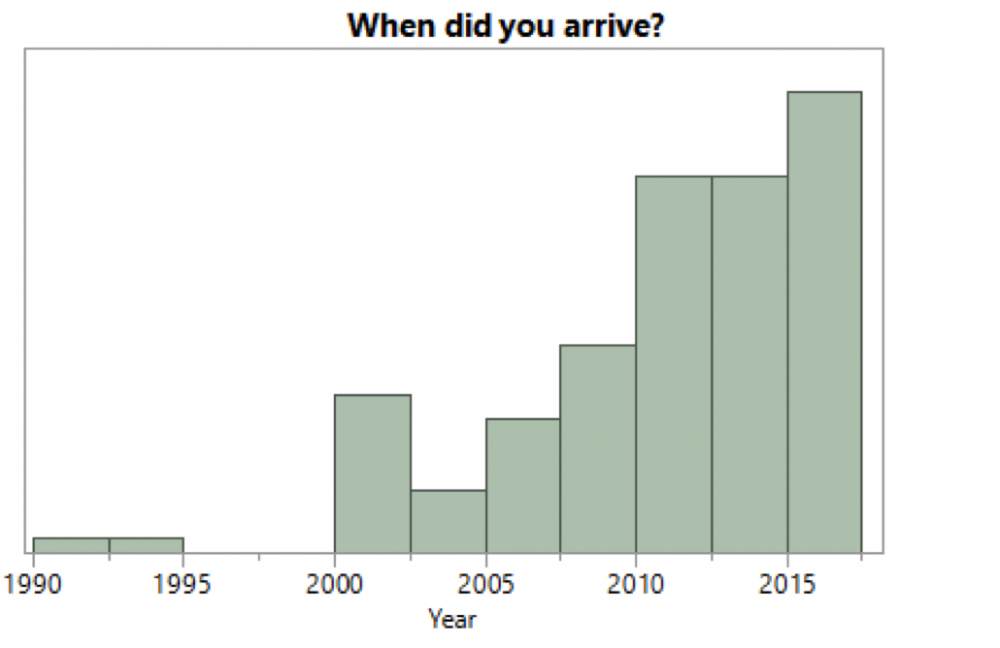

The end of the Cold War triggered a significant movement of Bulgarians outside of their country. It is believed that close to 2 million Bulgarians (out of a population of 8.8 million in the late 1980s) have experimented with working or studying abroad in temporary or permanent relocation. Major destinations for Bulgarian migrants have been the US, Canada and Western Europe, specifically Spain, Greece, Germany and the UK. Scholars studying trends in the UK specifically, observe that the movement of Bulgarians toward the UK became more prominent in the new millennium. Figure 1 speaks clearly of this trend.

Figure 1: Timing of Migration of Bulgarians in London

There are three prominent policy developments in the UK in this period that have influenced the behavioral patterns of Bulgarian migrants.

A 2001 provision in the UK migration policy has first allowed Bulgarian migrants to enter the country with working visas, under employment programs and business projects. This policy has been a major development that marked a sharp increase in the movement of Bulgarians to this country. A further policy elaboration in 2002 reaffirmed this selective opening of the UK market and created separate conditions of entry for citizens from Bulgaria and Romania. As the two countries were left on the back burner for EU accession at the time, the policy defined Romania and Bulgaria as countries of a homogenous category (A2), whose citizens were granted separate rights from those ascribed to citizens from the rest of their Eastern European neighbors (A8), which joined the EU in 2004 (Nyggaard, Pasierbek, Francis-Brophy 2013).

Bulgaria’s accession to the European Union in 2007 served, on the one hand, as the groundwork for another significant shift in the labor rights and the status of the Bulgarian community in the UK. On the other, it allowed for the arrival of another wave, which escalated in the mid-2010s that came on the heels of the 2008 global financial crisis. The effects of the 2008 financial crisis were especially taxing on southern European countries, Bulgaria included, and provoked both new mobility from Bulgaria, but also a relocation of Bulgarian migrants, who have previously sought employment in Greece, Malta, Spain, Italy or France. Even after Bulgaria and Romania were admitted to the European Union in 2007, and the visa regime that regulated access of their citizens to the UK was discontinued, the UK authorities chose to retain restrictions on labor rights for A2 individuals, sustained until the end of 2013 (Maeva 2017).

It is these policy conditions that had foremost impact not only on the size of the Bulgarian community in the UK but also on Bulgarians’ status and employment opportunities, their motivations for migration, interaction with other communities, and how they came to be perceived by their host country. In turn, the view that the British public formed of the community had a major bearing on how Bulgarians themselves integrated in the British society (Maeva 2017, Fox, Morosanu, Szilassy, 2012).

The logic that informed the immigration policy towards Bulgarians (and Romanians), and which in fact was justified in restrictions, had a significant influence on the image of Bulgarians and Romanians in the British media (Fox, Morosanu, Szilassy 2012, Mc Dowell 2009, Parutis 2011). In turn this image absorbed another layer of culturalist perspectives and motives for exclusion, which framed the British public view of these communities.

The most troubling feature of the British media perspective relevant to this moment is the high criminality and deception attributed to Bulgarians and Romanians. The repeated reporting on increasing (and exaggerated) “numbers,” “floods” and “crimes,” used both in official government documents and in the media not only lumped-summed these two immigrant communities together, but set them up as a “nuisance” and a “problem” for public life (Markova Black 2007, Mc Dowell 2009, Parutis 2011). To be sure, the so-defined features of Bulgarians and Romanians follow a predictable pattern, evident in other countries with large immigrant communities, in which one or few groups of ‘foreigners’ come to be seen as responsible for the country’s problems.

After 2013, this community was caught unwittingly in the crossfire of an especially heated immigration debate around Brexit, feeding off of public discontent and strong activity of the opposition. Bulgarians and Romanians have been collectively sneered with reference to perceived combination of cultural and social traits. This form of bias is still highly discriminatory, even if not directly versed in common understandings of racism (of quasi-biological labels and insult). It offers perhaps a less overtly aggressive narrative and yet that still attributes the issues surrounding migration to the essential characteristics of migrants themselves. The social bias from negative publicity casts a second layer of limitations on the integration success of migrants.

Employment patterns

The way in which immigration policies and social bias have impacted on the prospects for employment of Bulgarians are clearly seen in a pattern that does not reflect the actual educational credentials and skills of this community, which is visibly higher than the jobs they occupy.

This unfavorable outcome of the policy regulations is well observed in available statistical data that shows a very small number of highly-skilled laborers who entered UK from the A2 countries in the first decade of the new millennium, and over representation in the self-employed category (i.e. jobs in the construction and cleaning sectors, or in seasonal agriculture and food processing industries) (see a selection of data available here: Maeva, 2017, based on employer issued permits).

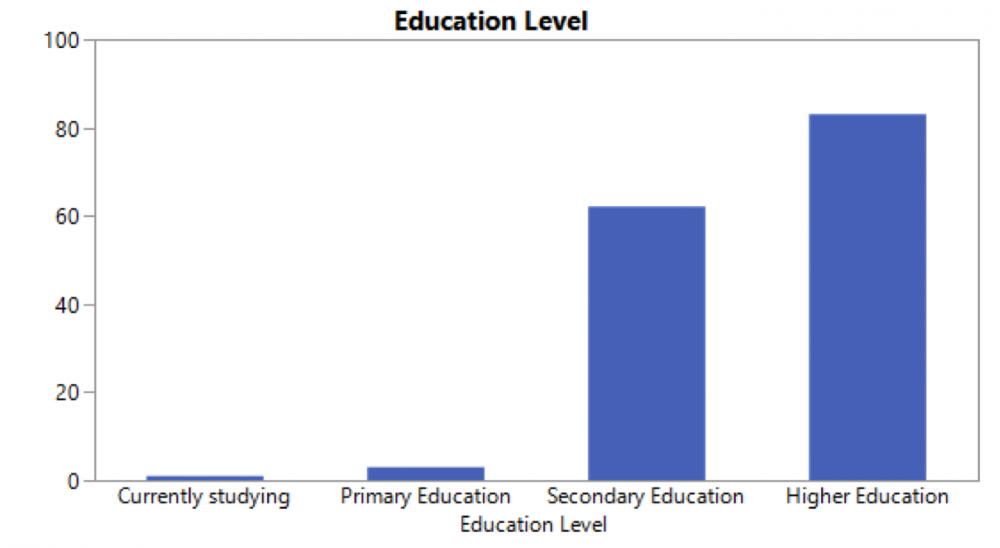

The selective access to the labor market, which the restrictions in immigration policy on A2 laborers geared, ended up pushing Bulgarian migrants towards the lower end of skills on the job market: jobs officially in demand, yet in principle deemed unattractive by locals. In addition, Bulgarian (and Romanian) immigrants have found themselves ‘below’ the status attributed to migrants coming from other Eastern European (A8) countries. This was unfortunate as it set apart as rivals and competitors communities that otherwise have much in common in their cultural ancestry, communist past and social experiences that can only benefit from mutual support. Scholars in the field have further noticed how in effect A2 workers have come to replace low-skilled arrangements, previously reserved for workers from outside the EU11. (Maeva 2017, Parutis 2011) This particular placement on the UK labor market also comes with a loaded culturalist bias and outright racism felt in Europe overall today towards immigrants from outside of the EU. The combination of the negative media coverage and placement in undervalued jobs affected greatly the success of the Bulgarian immigrants finding better opportunities on the UK labor market, especially in the period prior to 2014. Scholars notice that this particular set of structural conditions for laborers from Bulgarian (and Romania) lead to a decrease in the abilities and knowledge of these immigrants (or to “brain loss”), which is an unfortunate development for both, the host and sending countries, equally positioned to benefit from migration (Fox, Morosanu, Szilassy 2013, Maeva 2017). Figure 2 demonstrates the high education level of respondents in this survey.

Figure 2: Education Level of Bulgarians in London

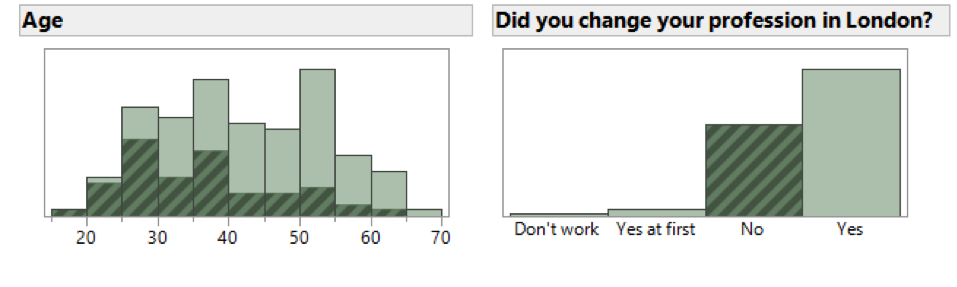

The sample of this study similarly reveals a significant number of Bulgarian immigrants in London who held much higher educational credentials than those required for the jobs they were able to secure. 83 out of 149 respondents held bachelor’s degrees or higher, and 62 out of 149 have finished secondary school. The adjustment to lower-skilled jobs they had to meet, was justified by many, as the prize immigrants were willing to pay in exchange for being able to care for dependents and facing challenges with English. At the same time, they acknowledge that employment in jobs undesired by Britons, but still in demand, makes them feel they have a visible contribution to the UK society.

Migrants in our sample, often underplay the burden of this detriment, as over half of the respondents mentioned only their poor knowledge of English to have impaired their ability to find a better job or better position in the UK society. Furthermore, few were able to pursue opportunities to improve their educational credentials or language skills, mainly due to the long working hours, associated with their low-end jobs or two jobs maintained at once. It is worth noting, that despite the work restrictions, some Bulgarians in our sample have managed to progress well in London’s business life: half of the ‘self-employed’ category were owners or managers of their own companies. Finally, only 4 out of 151 people are currently without a job. This is a remarkable achievement that stands in stark contrast to the stereotype that envisions migrants as a burden on the public coffer of their host societies.

Notes on socialization and integration

The immigration controls pertinent to Bulgarians, while motivated by an economic reasoning, still produced both employment limitations, as well as social bias, and racialized effects that frame the overall integration patterns of this community (Fox, Morosanu, Szilassy, 2012). For once, the general perception of Bulgarians in the British media to which we alluded earlier, as a community incomplete in being European, and having an equal status and associated rights, is internalized by this community members in a form of self-isolation and even shame. Rarely do they think of themselves, in their very private existence, as rightful contributors to the UK economy and society.

Figure 3: Age and Profession changes since arrival

In the study this is well reflected in the paradox that while most Bulgarians have found support in their adaptation from other Bulgarians, friends and family members, they still hold back from organizing on the basis of their group identity or taking part in community-based initiatives. Of concern is certainly the worry that such collective efforts might bring additional attention to their ethnicity that is already negatively sanctioned in the British public sphere. Some migrants have already internalized such bias in their own attitudes towards their own community and in wanting to distance themselves from the group. They wall themselves in more private existence within a circle of select friends. Many were willing to comfort themselves with the idea that the stereotyping is rather an exception for a country, temporarily frustrated by the very many unknowns surrounding Brexit and one that they otherwise applauded for its rich multicultural traditions.

Major trends by age, gender and education

Most migrants in this study of a sample from 151 individuals have shared that they have adapted relatively well to their new way of life in London upon moving here. Migration has posed emotional pressures, as did the need to learn English, but Bulgarians received support primarily from friends and colleagues in their early years, and by family and friends when they grew older. Over 100 of our respondents described themselves as happy, with other mentions of feeling ‘calm’ and ‘a citizen of the world’ after coming to London. They also recognize that they have become more sensitive to the inequalities in the world at large, they have come to interact with many more nationalities, especially outside of the EU, and have become more tolerant overall. For that they see London as a great cultural and social ‘melting pot’.

Up until their 50s, by far the most common activity for migrants as per inquiring in our survey is to go to the gym, followed by interests in visiting theatres, cinema, concerts and local libraries. Bulgarians of all ages are nevertheless reluctant to participate in associations, perhaps carrying such passive civic culture with themselves from Bulgaria.

In personal terms, most Bulgarian migrants in our sample assess that their being in London has changed them for the better, as they became more ‘tolerant towards diversity’, ‘polite’, ‘organized,’ ‘calm’, and ‘busy’ for the positive (effective in their business pursuits) and for the negative (‘nervous’ and ‘stressed’).

The majority of migrants is not excessively worried about Brexit, and has not been considering a change of plans, even if anticipating that most changes still lie ahead. Nevertheless statements about discrimination of Bulgarians after Brexit occur quite often, as well as expressed wishes that Bulgarians and other East Europeans are treated on their merits. In this regard, many have commended the Mayor of London for keeping London a tolerant place, while some even encouraged him to work for introducing a second referendum. Some were aware that such dynamics of tolerance maybe quite characteristic for London only, but not outside it in the entire UK.

The older one gets, the more likely it is that they have migrated prior to 2014, that they did so to join family, experienced issues with adaptation, especially with mastering English, maintained deeper contact with their neighbors, and had more critical messages about London as a busy city.

There are clear trends that crystallize when looking across generations, discussed in more detail and with vivid quotes from towards the second half of this report. Those in their 20s have different levels of education, most notably acquiring new knowledge and skills. Many of those who came to London after 2014 arrived to study. By far they feel secure in their neighborhoods, maintain little relationships with neighbors, but consider themselves well adapted, and wish to be treated more on their merits rather than as ‘East Europeans’.

Many of the Bulgarians in their 30s migrated prior to 2014. They are educated and work very hard as many of them work full time, even some do so over time. Two groups are crisply noticeable, that of the highly-skilled professionals and another of low-skilled workers. Both groups feel well adapted.

In the cohort of their 40s, more than half migrated prior to 2014. In our sample they are the most educated of all age cohorts, yet unfortunately among many of them the high educational credentials have not always translated into equivalent job opportunities, leading to professional “downgrade”. While some shared feelings of stress, weighting over their first experiences in London, the procurement of ‘blue card’ status (full access to the labor market), their hard work and perseverance have brought new opportunities, more of their choosing. This is the only generation, for which reasons for immigration of political nature come up as well, as some disliked how Bulgaria is governed and wanted a better future for their children. They pointed out also financial reasons and wish to be remunerated well.

The general patterns of employment in our sample shows that younger immigrants tend to have fewer problems finding a job similar to previously held positions in Bulgaria, while many of our older respondents have accepted their diminished employment status and remained with their first arrangements. Bulgarians who came before 2004 in general also shared having more difficulties in the recognition of their diplomas and job credentials, which can be explained by the lack of understanding of the credential systems of countries in Eastern Europe at the time, when they were not yet members of the EU.

Therefore, the cohort in their 50s occupy more manual labor jobs than younger generations. Many of them joined a spouse who decided to move, became employed prior to travel, or needed to migrate to find financial solutions to a challenge back in Bulgaria. While feeling well-adapted, this generation voices more problems with adaptation. The cohort of the 60s mostly came to join their children and be close to family.

Some trends are further noticeable in our sample related to gender and educational differences. Women express more concerns after Brexit, as they notice inflation, rising costs of living as well as discomfort triggered by what they see as heightened sensitivity and intolerance towards migrants. Educated women from Bulgaria have arrived mostly on their own in the UK, in search of professional realization. Many learned English already prior to their settlement here, hence they tend to socialize with wider circle of individuals, a mixture of internationals and Brits, as well as Bulgarians. Changes they see in their personal traits and experiences are qualified as positive, they have become more tolerant, patient and productive. Relatives from Bulgaria are what mostly causes worry as women traditionally carry more family responsibilities towards elderly and kids in Bulgaria. Those with families and kids in London engage in local programs and activism via the schools their children attend in London.

Educated men exclusively underscore their professional realization as the main motivation behind decision to migrate. They socialize in mixed environment of friends and colleagues, and mostly report not having issues with adaptation. Life in London has also made them more patient and tolerant, they acknowledge feeling sometimes overworked, but still are positive about their experiences. Some pointed to housing in London as a major worry. They do not notice much change after Brexit and do not have plans to change course.

The overwhelming majority of women with low-end jobs have high school diplomas and they came to London because of challenges back home. Many work as housekeepers, babysitters, care providers and “personal assistants”. They managed to find jobs quickly despite some emotional difficulties adjusting to the new employment. Language proved to be a big barrier, yet almost everyone said they are comfortable living in London and their expectations were met, as they can support families in London and back home. Many reported low self-esteem upon arrival, which they proudly share they came to overcome later. They feel invigorated, more self-secure because they managed on their own, and freer to explore further options for self-growth. In London they report to have become more self-disciplined, more tolerant and respectful of others’ differences. They report witnessing discrimination (increasingly so after Brexit) against Eastern Europeans, however they are also cautious sharing they have suffered such biases personally. The overwhelming majority works hard and socializes within the Bulgarian community.

Men in low-skilled occupations, on the other hand, while oftentimes arriving through pre-arranged contracts, share difficulties adjusting to life in London, finding new jobs and place to live. The majority came because of financial difficulties back home, mostly alone or with friends. Some were later followed by families. These interviewees shared they had no time to communicate outside of their closed groups of friends, mostly Bulgarian. They appreciate the more orderly life and disciplined labor rules but had difficulties with documents and their language skills. This stratum is bothered by high-criminality, and negative attitudes towards Eastern Europeans, beggars and quarrels on the street. They also have no intention of relocating from London, if possible.

Detailed analysis of trends in the age cohorts

In Their 20s: Explore the World, Improve Education

In this age cohort 28 people were interviewed: 11 women, 16 men and a person who claimed non-binary gender.

|

Gender |

Primary school |

High School |

University (BA and MA) |

|

Female |

n/a |

6 |

4 |

|

Male |

2 |

8 |

6 |

The professional occupations of Bulgarians in their 20s differ between jobs such as a marketing or public relations coordinator, accountant, sales representative, teacher, programmer, and student attending a London university; and jobs requiring manual labour, such as a cook, car-mechanic, construction worker, barman, and stage worker in the theatre. There is some precarity in job security observed among respondents, who claimed to work part-time or for more than one employer at the time. Many claimed that it was not necessary for them to change their work specialization upon arrival in London, and they have acquired such earlier in Bulgaria.

Most people in their 20s migrated after Bulgaria joined the EU in 2007 with the number of arrivals increasing greatly after work restrictions were abolished in 2014. It is remarkable to see that many of these young people have moved to London alone (13), or with a partner (7). Such trend speaks well of the independence of young Bulgarians and the willingness to rely on their own efforts as family dependencies are less pronounced among this age cohort.

Many came without pre-determined expectations about their new life which possibly helped them adapt quicker. Some experienced difficulties in the beginning, in particular with the emotional pressure to adapt to a new society and the separation from family and friends. Respondents mostly with primary school and high school education pointed out to a challenge to acquire the English language. Some found it challenging to ‘get adjusted to the fast pace of life’. Yet, by far the majority found that they adjusted very well. The following statements speak for themselves: ‘I am free to be myself’; ‘I feel relatively secure’; ‘I feel wonderful’ and ‘I like my way of life’. On the whole, the majority in this age cohort found that their lives have changed for the better after moving to London. They admit to have become: ‘more organized’, ‘more tolerant towards others,’ and ‘polite and quick.’

Going to the gym is by far the most common activity in this age group. Some go also to the library and visit theatres, galleries, clubs and concerts. More than half know their neighbors although most of these relationships have been deemed ‘distant’, mirroring the mainstream British society, and life in London as a mega-city. Most lead active social lives with 18 respondents sharing that they have friends from a variety of nationalities, while the rest were interested to connect to Bulgarians only. One person made an explicit statement that they like to stay away from other Bulgarians. The majority of the interviewed argued that they feel very good and secure in the London borough in which they live, with sporadic voices speaking about the presence of some ‘questionable individuals’.

Regarding Brexit, there is a presence of silence. Only 3 respondents found that there are changes in their experiences: ‘I feel neglected at my job, because I am from Eastern Europe’, and ‘the hotel business I work in has felt it, because of the lack of personnel’. The rest felt quite unruffled about their future after Brexit, ‘especially for the people who are already here’, and did not consider alternatives to change their plans.

In Their 30s: Super Busy

Altogether 43 people were interviewed in this age cohort: 25 women and 18 men.

|

Gender |

Primary school |

High School

|

University (BA and MA) |

|

Female |

n/a |

8 |

17 |

|

Male |

2 |

8 |

8 |

The professional occupations of this age cohort is skewed towards the highly skilled migrants with professions such as university professor, teacher, designer, accountant, tax specialist, engineer, consultant, manager in construction, photographer, dental practitioner, and others. Low-skilled jobs are primarily in cleaning and housekeeping services, mostly among women, who work either on a full time or part-time basis. Some men work in construction and as lorry drivers. These respondents work usually full time and are predominantly employed through one employer (34 people: 19 women, 15 men), hence largely enjoying job security. None of the interviewed claimed that they are unemployed, while 9 people claimed to work on a part-time basis.

There is an interesting phenomenon in this age group, not observed among the younger generation: 4 people with full time jobs argued that they also work additionally part-time, i.e. more than 36.5 hours per week. Such jobs are related to consulting and housekeeping services. About half of this group claimed that they needed to change their original profession in order to find their current occupation. Some of them had to be ‘downgraded’ in their current job compared to their previous education level; while others found their current jobs after an educational ‘upgrade’ while in London.

Half of the Bulgarians from this age cohort migrated prior to 2014 and half of them in this year’s aftermath. Reasons for migration oftentimes relate to a desire for a personal or professional expansion beyond a comfort zone: ‘I came here to improve my education’, ‘to get a better professional opportunity’, for ‘better professional realization,’ ‘I wanted to try something new’, to ‘see the world, and travel’. Many also point out that they wanted to find a job with a better payment, and came for ‘financial reasons’.

Similarities with the younger age cohort continue: most people in their 30s came alone or with a partner and faced similar adaptation challenges: emotional stress due to separation from their families, ability to speak English and what people refer to as ‘the British mentality’. Bulgarians of this age group are also mostly absent from taking part in local associations however they like going to the gym and visit theatres, cultural events and talks. Their contacts outside work also mirror their busy life-styles: many socialize with their colleagues from work or university after working hours, and only ¼ of the interviewed claimed that their contacts are among Bulgarians only. Most of the interviewed maintain only polite relationships with neighbors, some having no time due to their busy life.

This age cohort also finds that their new life in London has changed them for the better, and that they have become more ‘tolerant towards diversity,’ ‘patient,’ ‘more open’, ‘exposed to more travel,’ ‘walking more often than earlier in Bulgaria’ and visiting more cultural events, there are also statements indicative of closing socially, due to extremely busy schedules: ‘I am becoming more productive due to the quick pace of life, but also more mindful of my private time, which is a limited resource.’ Interestingly, many people came with bigger expectations for themselves than what actually happened, in contrast to the people in their 20s which had no expectations. This is evident in some of the negatives they report about their lives in London: ‘polluted air, long commutes, expensive housing and stressful way of life,’ having mixed feelings about London, and starting to consider to live in a smaller place, where the rent is not that high.

Brexit seems to be a topic for people in their 30s as one person argued: ‘A change started being felt even before the Brexit referendum, during the Brexit campaign. There is no way it would feel good when Bulgarians are always featured negatively in the news, or to look at slogans and posters that advocate that foreigners are chased away, and to continue to feel welcome.’ Another person argued: ‘Sometimes I feel how people start looking differently at me, once they learn that I am Bulgarian.’ Although the majority does not plan to move, most of the people are still concerned that changes are forthcoming.

In their 40s: Caught Between Being Busy and Worrying about the Future

33 people were interviewed in this age cohort: 18 men and 15 women.

|

Gender |

Primary school |

High School |

University (BA and MA) |

|

Female |

n/a |

2 |

13 |

|

Male |

n/a |

8 |

10 |

As the figure above demonstrates, this age cohort is also skewed towards the highly educated. Job occupations include: an investment banking programmer, accountant, teacher, data protection consultant, manager, sales consultant, while many others work in house-keeping, construction and trade (with Bulgaria). More than half of them (28) have migrated prior to 2014. There are several contrasting aspects from the generation of the 30s. This group, enjoys a relatively high level of job security. There is also some individual entrepreneurship and no unemployed. Many in this age cohort were not in a good position to translate their work experience and degrees from Bulgaria directly into employment in the UK, and needed to undergo certain occupational “downgrade.”

For the first time in this age cohort reasons for migrating also relate to how Bulgaria is governed and how it cannot secure a better future for their children. Others were weary of living check-to-check in Bulgaria. Hence, here the reasoning becomes less about education, but more about translating education and other experience into respectful remuneration.

Regarding adaptation to the UK society some dynamics are also different, namely opposing perspectives on experiences, especially concerning the beginning: some found it really difficult to adapt, while others really easy. Finding job was quite difficult for some and relatively easy for others. Problems with mastering the English language are considered by far the most difficult to overcome, followed by an emotional burden of living in a new society. Polarities are visible when discussing how they feel in London as well. Some feel ‘enriched’, ‘feeling good in a large and cosmopolitan city’, ‘on another planet’, ‘enjoying human rights’, ‘privileged to live in one of the world’s capitals’, a ‘citizen of the world’, and ‘I think of London as my home’, among others. Yet, others feel differently: ‘I am managing the problems of my household’, ‘I still feel like a foreigner’, ‘feeling good but the city is overpopulated’, ‘it is not very cozy here, if I find a permanent job, I would move to a smaller city outside London’, ‘the distances and the crowds overwhelm me sometimes’, ‘I want to go back to Bulgaria’. Some in this generation considered alternative migration destinations (Spain, Italy) prior to coming to London, but usually spousal deliberations turned the path towards London.

Regardless, this cohort sees positive changes in themselves overall, becoming more ‘tolerant towards diversity’, ‘better mannered’, ‘more motivated’, although also more ‘nervous’ and ‘stressed’. Although this generation is similarly less engaged in associational activities, prefers sports, it is also more inclined to go to the library, and cultural events. Families with children were more limited on time for recreation. In contrast to the younger generations, this group has lived longer in one place and keep deeper relations with neighbors, not least because some of them are Bulgarians. They feel relatively secure in their neighborhoods, mentioning also the good city infrastructure, and only occasionally some aspects of insecurity. Because of family obligations they maintain smaller social circles, often with other Bulgarians.

The repercussions of Brexit are also conceived here in personal terms: ‘In our family we all have British passports’, therefore formally Brexit is not of concern for British citizens. But they also share a sense that many are ‘confused’ about Brexit. An entrepreneur argued: ‘I am having more work now, since others are leaving for Bulgaria; but after Brexit, my business will become impossible if the goods are taxed differently’; this would result in a loss of business and jobs. Some observed change in attitudes to foreigners and increasing cost of living. One person argued: “Only in some places outside London there is a clear disdain against foreigners. London remains unchanged regarding Brexit, which is bringing hope. Yet, I am working in an industry that will undergo changes after Brexit, which will most probably necessitate the cutting of jobs, and could cost my job as well’. Many are nevertheless considering no specific moves at this point of time.

In Their 50s: Joining Family, Aiming at Financial Security

In this age cohort 38 people were interviewed: 19 men and 19 women.

|

Gender |

Primary school |

High School |

University (BA and MA) |

|

Female |

n/a |

11 |

8 |

|

Male |

n/a |

10 |

9 |

By contrast to the cohorts of the 30s and 40s, skewed towards the highly skilled, the educational level of those in their 50s is almost equally divided between people with high school and university education. Although a larger number works full time (30) with one employer (27), there is more job precarity, as a good number is either working part time (8) or for more than one employer (5), usually getting work arrangements for up to a full working day, or declare themselves self-employed (6). There are occupations such as a business and technical manager, consultant, IT specialist and administrator, yet the majority of jobs are in the low-skilled service industry: in housekeeping, waiting tables, and working as a nanny for women, and as a carpenter, constructor, in a car-wash, and driver for men. Nobody declares themselves as unemployed.

As in the cohort of the 40s, the bulk of the migration here is prior to 2014 (31) and not thereafter (7). The reasons to migrate to London are usually twofold: to join family members who have acquired opportunities to work, and to secure a better financial future.

Respondents from this generation also assess themselves as well adapted to their new life, mostly because friends and family have helped them. They nevertheless point out to difficulties acquiring the English language, and experiencing challenges with the entire change of life. In this age cohort there is no such exaltation about positive changes that life has brought to them after migration. Many are still happy with the changes, and particularly point out to having become more tolerant and ‘calm’, while others have not found any particular change, or have become more critical. One person even argued that they became a racist. The majority is not interested in participating in associations and matters of interest to their neighborhood, and if at all having free time, go swimming alongside to the gym, and more occasionally the library, cinema, concerts, and theatre, as well as Bulgarian restaurants. One person argued to be a member of the Tory.

Most feel secure in their neighborhood, yet comments are made on the ‘high criminality’ in the city, ‘local gangs’ and crowds walking around who have consumed drugs, or ‘small-level thugs’ who go away without consequences. Some find the city to be dirty, overwhelmed by people, and feel the spike in food prices. Respondents in this age group also socialize mostly with other Bulgarians and report relationships with other nationalities rather occasionally, mostly work-related. Yet, their connections to Bulgarians are not mediated through institutions, but mostly established on an individual basis.

Although many have not felt significant changes after Brexit, this generation worries more. There is ‘an anticipation that Brexit will have consequences on the medium and small business’; some people saw ‘plunging of work’ in volume and opportunities. Most people plan to stay in London if possible but consider alternatives in the face of insecurity after Brexit.

In Their 60s: Close to Our Children

From this age cohort 9 people were interviewed: 4 men and 5 women

|

Gender |

Primary school |

High School |

University (BA and MA) |

|

Female |

n/a |

n/a |

5 |

|

Male |

n/a |

2 |

2 |

This is a small sample of respondents, where higher education is visible, yet job occupations are the most precarious. Most work as support personnel: in hospitals, cleaning or taking care of children, often part-time or by being self-employed. Most of them have moved to join other family members, take care of grandchildren, some wanted to earn additional income. The majority had difficulty adapting in the beginning and with English. Some feel good as they have learned new things and moved closer to children. They like to visit the library, as well as cultural activities, do not participate in associations or neighborhood activities, although they help their neighbors ‘with the mail’ and maintain polite relations. Most socialize primarily with Bulgarians, again on a personal and not communal basis. They feel relatively secure in their London borough, and are happy that their children have good chances to grow.

Conclusion and Messages for Mayor Sadiq Khan

It is evident Bulgarians have tried to adapt as best as they could in their new home London. The majority works hard and socializes with other individuals from the Bulgarian community, albeit mostly through individual connections, not on a communal basis.

Bulgarians are content with their ‘new’ lives and do not plan to relocate, which means the pros they see from living in London outweigh the cons. With that said, we think there are a number of simple and effective measures that can be taken to improve Bulgarians’ integration in the larger London community and ensure an ever flourishing relationship between Bulgarians and the other nationals and internationals living in London.

Language is still a major barrier for Bulgarians to unveil their true potential whether in terms of work capabilities or in developing relationships with members of other London communities. And while English courses are available in abundance today, free language courses in community centers might stimulate the building of cross-cultural exchanges and contribute to socialization and integration. For now, even if available, such courses are not on the minds of Bulgarians: they are simply too busy, shy or not aware of them. A more concerted effort to engage the closed social circles of Bulgarians with lesser command of English would be a beneficial gesture of support and recognition for this hard-working contributors to British society.

Following habits formed at home, busyness at work or at home and the closed social circles of some Bulgarians, there are relatively few Bulgarians participating in civic activities and voluntary work so central for Western societies. Most Bulgarians are friendly and willing to participate actively in their local communities if approached correctly. Some ways to approach Bulgarians would be visiting local (Christian Orthodox) churches and other places where Bulgarians worship, Bulgarian shops and Bulgarian Sunday schools which are natural accumulation points for Bulgarians living in London.

The above mentioned barriers contribute to Bulgarians feeling excluded and sometimes even discriminated from public life in London and the UK. Negative press image, people’s prejudices and the fact that the Bulgarian community is quite small compared to other immigrant strata, all contribute to the feeling of exclusion. An active campaign to make the Bulgarian culture and heritage more visible by publicizing cultural events or encouraging cultural festivals (e.g. ‘Bulgarian food day’) will counter some of the negatives including discrimination, and fake and exaggerated news, and will help to further develop London’s cosmopolitan image and inter-communal coherence. With this study we intended to shed more light on the Bulgarian community in London and thus make it more integral to London’s public life.

Bulgarians like many other citizens of London face problems with the over crowdedness of the city, pollution, expensive public transport, living costs and high rents and also public services like the NHS. Bulgarians have also started worrying about their safety following the recent accidents in London. Some of the respondents also urged for a second Brexit referendum to make UK once again part of the big EU family.

It is worth noting that more than 40% of the written comments for Mayor Sadiq Khan and his team were ‘wellbeing’ wishes and ‘thank you’ for the fulfilling life they are living in London. Bulgarians found themselves living amongst ‘great and real Europeans’ and in what a poet called ‘a City of Love’.

References

Maeva, Mila 2017. “UK Policy Towards Bulgarians and Stereotypes about them since 1989”. In: Euxeinos 22

Balch Alex, Ekaterina Balabanova. “Ethics, Politics and Migration: Public Debates on the Free Movement of Romanians and Bulgarians in the UK, 2006–2013.” Politics 36, no. 1 (2016): 19-35.

Fox, Jon, Laura Morosanu, Eszter Szilassy. “The Racialisation of the New European Migration to the UK.” Sociology 46, no. 4 (2012): 680 - 695.

Markova, Eugenia, Richard Black. New East European Immigration and Community Cohesion. York Publishing: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2007.

McDowell, Linda. “Old and New European Economic Migrants: Whiteness and Managed Migration Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35, no. 1 (2009): 19-36.

Nygaard, Christian, Adam Pasierbek, Ellie Francis-Brophy. “Bulgarian and Romanian migration to the South East and UK: profile of A2 migrants and their distribution. Report prepared for the South East Strategic Partnership for Migration.” November 2013. http://www.reading.ac.uk/web/ files/press-office/Migration-Dr-Christian-Nygaardfull- report-Nov2013.pdf

Parutis, Violetta. “White, European, and Hardworking: East European Migrants’ Relationships with Other Communities in London.” Journal of Baltic Studies 42, no. 2 (2011): 263-288.

“Report. Bulgarians & Romanians in the British National Press: 1 December 2012 - 1 December

2013”. Migration Observatory. Accessed 16 December, 2016. http://www.migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/reports/bulgarians-and-romanians-british-national-

press.

Appendix A: Questionnaire

- Demographics

- What is your Age/Sex/Ethnicity?

- Do you work and what is your profession? Full-time or Part-time? How many employers do you have?

- What is your education level?

- Did you have to change your profession after coming to London?

- Why in London?

- When did you move to London?

- Did you come here alone or with someone else?

- Did you have any friends or relatives in London when you arrived?

- What were your expectations and goals when you came to London? Have they changed now?

- What was the most important thing, person or institution that helped you adapt to life in London?

- Was it hard to find work, education or a place to live?

- What was most difficult during your adaptation (learning the language, education recognition, document legalization, emotional burden, other)?

- Do you think you are well adapted to life in London? How would you compare yourself to other Bulgarians?

- How do you feel as a citizen of London?

- Were there alternatives to living in London?

- Do you find any changes in your behavior since coming to London? How would you classify those changes?

- Do you participate in the public life of your London neighborhood?

- Where do you live in London and why did you pick this neighborhood?

- Do you visit the local library, sports centre, theatre, etc?

- Are you a member of local community organizations like clubs, associations or meet-up groups?

- Do you know your neighbors? Do you want to know then? If yes but you prefer not to maintain a relationship why is that?

- What is your social circle in London?

- Do you have friends and acquaintances outside of work?

- Do you have spare time for socializing or for going out? If yes, where do you go?

- Would you describe your friends as mainly Bulgarian? Mainly migrants? Mainly British? Mainly internationals? Explain why?

- If you maintain contacts with the Bulgarian community in London what is the main reason for that?

- How safe do you feel in your neighbourhood?

- Is there anything that makes you feel uncomfortable and why?

- Have you witnessed any change in your life after the Referendum?

- Have your plans changed?

- Is there anything you would like to tell Londoners or the Mayor of London?

Appendix B: Some messages to Londoners and the Mayor of London

'Try to integrate the Bulgarians in time before it is too late. Support the financing of events that promote Bulgarian culture, language and traditions and to offer integration courses if there are none.'

'I would like to say that for me, London is a unique city and I am extremely happy to have the opportunity to live and work here. What drives me in London is diversity and dynamics. The Bulgarian community in London, visible or invisible, is large. I would love to see more cultural events devoted to and related to Bulgarian culture.'

'I would invite Londoners to come to Bulgaria, to my village. I'll cook for them, treat them with homemade brandy and show them the local landmarks. So I'll thank them for their hospitality to me and my family here in London.'

'I thank Londoners for the colors they bring with them and for every new thing they teach me every day.'

'I would like to tell the Londoners that we are Bulgarians like them, but we are talking in another language. Sometimes I feel treated like a stranger I do not like it.'

'I am delighted that the city retained its international spirit and tolerance for migrants after the referendum (at least in my experience). I like that spirit of London.'

'They are great, it's great! Europeans everywhere! Pity! Hopefully they can handle the knife, gun and moped theft crime. Sad for the dead children, the elderly. I hope they will fight terrorism.'

'The main factor for starting work should not be English, because if a person is good at work, he does not need to know English to do it.'

'Much of the streets and public places outside the center are pretty dirty. I hope this improves. Driving is much easier than in Sofia, but: There are huge bus lanes that are forbidden to simple drivers and most of the time are empty. They can be used in peak hours. Everywhere in hospitals, company headquarters, large institutions, I meet places of prayer for Muslims. So far I have not seen Eastern Orthodox place for prayer. I do not mind Muslims, but it looks more like the authorities fearing to not be accused of discrimination rather than of tolerance.'

'The city will be much more relaxed if the metro meets the transport needs of the citizens, for example, I use a Central line with outdated infrastructure overloaded as a whole fails to take on the capacity of travelers. The NHS Health System is also very subdued and fails to meet the needs of patients.'

'Let Londoners be healthy and keep the city clean. Mr. Mayor, I wish you good health and strong spirit and to improve the quality of the public transport as it's very expensive.'

'I would recommend a campaign to reduce the use of polyethylene bags, as they are doing in Bulgaria lately. I notice that too much is being used.'

'Your work as mayor of London is certainly very stressful and with many responsibilities that paying attention to our small community here in London is commendable. Thanks.'

'I would like to have more calls for participation of Bulgarian communities in London projects. I want the mayor to participate in Bulgarian events. My dream is for Bulgarians in London to become noticeable for Londoners and the mayor of London.'

'I'm not at this level in London at the moment. The mayor, I have written to him before, I will write to him again, if necessary. I want to thank him for the wonderful job and wish for a healthy health and success! He and his team are excellent!'

'I would like to have more opportunities to learn English under ISOL. Most colleges are not taught under this program, or they are insanely expensive. I would like to see London clean. Cleanliness is a priority only in the center. If anything can be done on th